|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| Extreme Makeover, Global Edition - Episode One |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | |

| Jul/04/2006 | |

What is the ideal global architecture of the global economy and political system? How would the economy be reconstructed in such a way that the global ecosystem could survive and support a thriving economy? What would be the appropriate global political structure? These are very complex questions, but unless they are articulated, neoliberal philosophy will continue to dominate intellectually, by default. Perhaps the reader is not familiar with the American reality TV shows entitled “Extreme Makeover” and, more recently, “Extreme Makeover, Home Edition”. The first series detailed a ghoulish set of extensive facial plastic surgery procedures, inevitably turning an ugly duckling into – well, something a little more palatable to the TV audience. The second series involves sending a family away from their run-down, or in the case of a show in New Orleans, devastated dwelling, only to come back a week or two later to every person’s dream home, the kind of thing that every American should be able to afford on their own, if it weren’t for the savaging of the middle class.

It has always been TV’s forte to sell unattainable dreams, whether within the TV show proper or via commercials. The philosophical advantage of the “Extreme Makeover” series is that it allows the viewer to see what ideally can be done with the structure (let’s focus on the house), without worrying about how to get from here to there. In the case of the house, the owners are not burdened with figuring out how to finance the reconstruction, or who to turn to for plans, or how to do the actual construction, although the audience can see the latter taking place. When thinking about global problems, it may useful to undergo a similar exercise. As readers of sandersresearch.com, and this series, “Taking the Long View”, are only too aware, the forces stacked against the people and ecosystems of the planet are immense. However, the crises affecting the planet are also immense; for a fine visual presentation of the problem of global warming, for instance, one can presently do no better than to see Al Gore’s movie, “An Inconvenient Truth”. Therefore, it might just be the time to have the “unmitigated audacity”, to use a phrase of Frank Zappa’s, to consider how the world could be put together in a better way. What is the ideal global architecture of the global economy and political system? How would the economy be reconstructed in such a way that the global ecosystem could survive and support a thriving economy? What would be the appropriate global political structure? These are very complex questions, but unless they are articulated, neoliberal philosophy will continue to dominate intellectually, by default. Neoimperial dreamsThe neoliberal, or neocon—let’s just call it neo-imperial philosophy—is constructed in order to justify the actions of the richest and most powerful. The main “scientific” underpinning of this ideological framework is neoclassical economics. The basic political goal of neo-imperialism is to eliminate government intervention in the economy—that is, intervention on behalf of the society as a whole. However, as has become evident in the Bush Administration, the neo-imperial ideal is to turn the government into a reverse Robin Hood institution, and to institutionalize corruption by taking money from the middle classes via taxes and shoveling it into the coffers of friendly corporations, via contracts, as most famously for the Vice President’s firm, Halliburton. The reason to call this ideology “neo-imperial” is because the part of the ideology that appeals, not to reason, but to the reptilian part of the brain, is the emphasis on militarism. In a strange way, the most sophisticated, or at least, totalitarian, culmination of militarism is the suicide bomber, who will not just risk his or her life, but will for certain lose his or her life, just because his or her superior said so.

The more “normal” call to arms, of the kind that ensnared many American soldiers in Iraq, has been perfected over the millennia to appeal to emotions that the state has been experimenting with during the course of recorded history. It is different only in degree from suicide bombing, because killing or being killed are highly immoral and against one’s self-interest, respectively. The ultimate goal of,

seems to be the establishment of a global elite that can use the nation-state’s military apparatus to enforce its will. There is an inherent contradiction in this program, however, because the military assets are still national while the elite attempt to create a global, non-national economy that they control. Of course, people have been trying to take over the whole planet since at least Genghis Khan,

who thought that world domination was the task to which he had been born. But up until now, the idea has been to achieve this domination by using the vehicle of the nation-state. To create a global, transnational elite who could agree to rule together – a global oligarchy – sounds like too great a task for the huge egos involved. A global elite, backed up by a predominantly American military, will not only be a difficult process of cooperation, it will also drive both human society and the global ecosystem toward collapse. The Bush Administration and the oil and coal industries are almost indistinguishable, and they will certainly not do anything to avoid global meltdown, either in the atmosphere or within the agricultural and water systems of the planet, as discussed by Lester Brown in his books, particularly Plan B 2.0. [1] What is quite perplexing is that the other power centers of the planet are not prepared to play hardball to make the Americans do anything about global warming. As can be seen in “Inconvenient Truth”, Shanghai and Calcutta would virtually disappear if sea level rose by 20 feet, which would happen if either Greenland melted, the West Antarctic Shelf melted, or some partial combination of the two. The often-muzzled top U.S. climate scientist, James Hansen, believes that the rise in sea levels caused by the melting of huge ice formations is the most important potential problem caused by global warming, and will kick in if the Earth’s temperature increases by only one more degree Centigrade (he is less pessimistic about the chances of changing economic activity to avoid more warming).[2] Apparently lower Manhattan would be lost as well – maybe the geniuses on Wall Street figure they can relocate to Midtown along with Morgan Stanley? The Europeans, who claim to be more “green” then the Americans, generate almost as much greenhouse gases as the Americans (27% vs. 30%, according to Gore’s film), and just endured a horrendous heat spell that killed thousands of people. Et tu, Europe? And what about the possibility, as Al Gore clearly shows, that a melting of Greenland would induce a European Ice Age of, oh, maybe 1000 years? Perhaps the elites of other regions are too busy enjoying their power to care about this sort of thing, a process partially explored by many historians, and most recently by Jared Diamond in his book “Collapse ”.[3] Faced with overwhelming problems, Al Gore is concerned that people flip from denial of global warming to resigned depression, from thinking that nothing needs to be done to thinking that nothing can be done. The problem, I think, is that humans think in terms of holistic images, what psychologists call a “gestalt”. Gore’s conundrum can be explained in terms of gestalts:

What they need is the image of an alternative economic system, one that is different than today’s and one that is survivable.

The Bush Administration would like to replace the average American’s image of the U.S. political system from one involving the Constitution and fuzzy images of the Founding Fathers to the image of the snarling Dick Cheney, a police state, and the smoking remains of the World Trade Center. There is another vision being foisted on the public, the image of globalization, the full victory of which would be the end goal of neoclassical economics. The average citizen is supposed to think that the world is completely uncontrollable, that his or her job is at the whim of inscrutable Chinese; that his or her physical safety is at the mercy of mysterious Muslims; and that his or her freedoms must be, or in any case are being, taken away by a militaristic state. The Importance of being continentalThe first task of a global extreme makeover is to construct an alternative image of how the world now looks and how it can look in the future. Once this image has been created, the next task would be to figure out how to get from here to there, obviously a gargantuan enterprise. The first basic element of a global gestalt is to understand that economies are continental or subcontinental, not global. This means that economies are not national, either, except when a country encompasses an entire region, such as China. The continents have been parked at particular points on the planet, at least in the time span of human history, and the structure of the geography of the continents has driven human history in the past and will do so in the future.

It used to be a common theme of mainstream political science to concentrate on the geographical determinants of international relations.[4] More recently, the biologist Jared Diamond wrote a book, Guns, Germs, and Steel ,[5] in which he attempted to answer the question “Why did Eurasia dominate the rest of the world?”. My interpretation of his answer is that the Eurasian land mass, because of its size, generated more species than the continents of the Americas or Australia, and two of those species were horses and wheat. Horses in particular were good sources of power for production and also filled the functional niche that would later be filled by tanks, that is, fast, intimidating, and powerful pieces of military equipment that overwhelmed societies that lacked horses, such as the Incas. Africa lost out to Eurasia because zebras, the equine species native to Africa, are too intelligent to be lassoed, and in any case the tsetse fly and other tropical diseases made massive agricultural complexes impossible. Predating Jared Diamond’s enquiry have been the activities of historians attempting to answer the question, “Why not China?”.[6] That is, China was clearly in a position to dominate most of Eurasia by around 1300 to 1400, but instead Europe filled that role. The answer seems to have something to do with proximity to the militarily-sophisticated peoples of the Eurasian steppes, whose rule over China provoked an isolationist backlash when the Mongolian overlords were expelled. On the other hand, Europe was too far away from the Steppes to attract Mongolian attention, and when the Mongols did once make their way almost to Germany, the Great Kahn(leader) of the Mongols died and the invading Mongols had to go back to pick a new leader, never to return. In addition, the Mongols colonized India, and with the Turks, who also came from the Steppes, subjugated the Middle East, leaving Europe as the only center of independent activity. Thus, it is that the luck of the geologic and sometimes historical dice has led to various societies thriving and others being torn apart. Britain and Japan happen to be islands, which helped repel invaders, but they were close enough to power centers to learn from and eventually dominate them. Geography does not determine history, a conceit often associated with the older scholars of geography-based international relations, but it certainly is important. The existence of container cargo ships, airplanes, and fiber optics does not decrease the importance of geography. The important question to answer about a particular geographic area is, is it easy to get from one place to another within the specific region? If it is, then goods and people can move easily within the area. This makes trade easier, but it also makes production easier, technological change greater, and the adoption of technological change quicker. Engineers, the industrial social butterfliesWhen people can move within a geographic space with ease, they can examine other people’s ways of producing things with ease as well. I suggested earlier that people think in images, and holistically. The same applies to engineers, who are, after all, people, and who profit greatly from visiting other engineers and experiencing the operations of machinery first-hand.[7] It’s one thing to read a description of how a machine works, and quite another to look at it, three-dimensionally, and to be able to interact with the machinery and note how it behaves as the environment of the machinery changes. An example of this interaction was noted long ago by the economic

historian Nathan Rosenberg.[8]

Rosenberg traced the way that innovations in machine tools, and the industrial machinery that machine tools produce, influence each other. By the mid-nineteenth century, machine tools were making possible the first great explosion of American industrial know-how, agricultural equipment. The mechanization of agriculture led the U.S. to become one of the great agricultural exporters of the world, as it is to this day. The interaction of the machine tool makers with the agricultural machinery makers, furthermore, led to improvements in machine tools as well. These improvements then made possible the next wave of industrial innovation, sewing machines, whose construction led to more advances in machine tool design, until by the late nineteenth century, machine tools were powerful and precise enough to lead to the development of the bicycle. Many of these bicycle makers went on to become automobile makers, including one Henry Ford. By the time production methods for bicycles had been seriously improved, the machine tools were available that would make possible the great boom in automobile making…which would lead to global warming, but that’s another story. Thus, because of the close proximity among the machinery makers and their customers, as well as between the goods providers and consumers, technological innovation was greater and quicker to spread throughout society. As I have written previously, the production of goods and services requires a complex assemblage of manufacturing industries, including the production of industrial machinery,[9] and this production also requires a sophisticated physical infrastructure of transportation, energy, communications, and water networks.[10] The U.S. had a great advantage in the 19th and 20th centuries, because it encompassed a continent-wide economic space with an excellent infrastructure and complete suite of manufacturing industries, governed by the same state and using the same rules. The great railroad-making ventures insured that goods and people could travel around the country with relatively little effort. Can we get no satisfaction?The other major geographic spaces around the world are also easy to crisscross. China’s coast, where the vast majority of Chinese live, is connected by sea and by an elaborate series of canals and rivers. The northern part of India is an easily traversable plain, and most of the population lives in one belt in the north. The Alps are the main impediment to travel across an otherwise flat Europe, and this ease of movement has always tempted would-be emperors, from Charlemagne to Charles to Napoleon to Hitler. Central Eurasia, known most recently as the Soviet Union, has been prone to consolidation since the Mongols, and also vulnerable to invasion because it is easy to traverse.

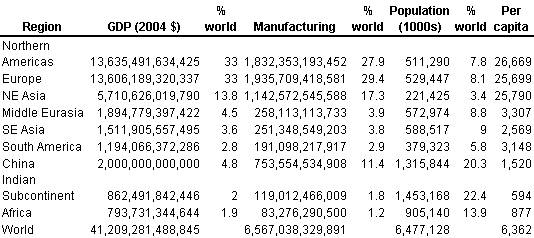

The Middle East, as well, has been washed over by conquerors, from Hammurabi to Alexander, from the Ottoman Turks to the Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld neo-imperialists, but this ease of conquest also made possible the founding and flowering of civilization. Empire makers often stop at the boundaries of these more easily administered regions. The German historian Dehio argued that some Powers, such as the Chinese, were “satisfied”, that they did not want to extend past their boundaries because their polities were a “natural” unit.[11] The Ottoman Turks settled into the administration of North Africa and the Middle East; going further afield involved crossing barriers such as the Black Sea and mountain chains. The political scientist David Calleo argued that part of the “German problem”, as the tendency to start world wars was termed, arose from the natural desire of European, and particular, German rulers to reason that the whole of Europe represented a logical unit, and that even as strong a country as Germany was somehow too small.[12] When Hitler and Napoleon managed to take over continental Europe, they impaled their empires by taking on another natural unit, the Russian Empire. World history, and the history of the global economy, is understandable in terms of geographically logical units that are defined by the geography of continents or subcontinents. If the continents were set up differently, there would be a different logic of world history. To risk a little abstraction, structure does not determine action, but it constrains some actions and enables others. The structure of the continents leads to various natural economic regions, and has enabled some regions to dominate others. This Old HouseThis first task of Extreme Makeover, Global Edition, therefore, involves trying to determine what regions make natural economic units. This project is wrought with all kinds of dangers, because many of the world’s hot spots are exactly between countries that are within a natural economic unit and are fighting for control. For instance, I would argue that Israel is part of a natural unit encompassing the Middle East. Pakistan and India should probably be part of the same unit. The problem is not to worry about potential problems, at this point, but to construct the image of a logical global system. At the risk of offending national sensibilities at this point, let me propose the following regions.[13] :

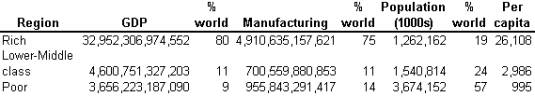

For the Northern Americas, I include North and Central America and the Caribbean. For North East Asia, I used Japan, the Koreas, and Taiwan; for the Indian subcontinent, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and India. SE Asia is everything else in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania; Europe includes all of Non-Soviet Europe plus the Baltic states; and my strangest grouping is Middle Eurasia, which encompasses the former Soviet Union, plus Turkey and the Middle East. In the next article I will go into greater detail concerning these units, but there are a few items that are immediately evident in the table. First, the Northern Americas and Europe have virtually the same percentage of the world’s GDP, and very similar percentages of world population as well as per capita income. Keep in mind that I have included such widely disparate states as Haiti and the U.S. in the Northern Americas, while Europe includes Albania and Luxembourg. Second, there seems to be a tripartite division of the world at the moment, from rich, to lower middle class, to poor, as shown in the following table:

The “Rich” are the Northern Americas, Europe, and NE Asia. With not even one fifth of the world’s population, they generate four fifths of the world’s economic activity. The next group is in the middle; but with a per capita income of about 1/9th of the Rich, they are certainly lower middle. These include the three regions of Middle Eurasia, SE Asia, and South America. Finally, there are the three large, poor, populous regions of the planet, with about 1 billion people each, China, India, and the disunited Africa. While China has eliminated much of its most brutal poverty, it still has a long way to go (I will discuss varying estimates of its wealth in the following article). With over half the world’s population, this group does not even generate 1/10th of its annual production of wealth. The per capita income of its 3.7 billion people is about $1,000, which is 1/3rd of the lower middle class and about 4% of the rich. The lower 80% of the world population, and the part of the Rich 20% that are poor, obviously should have a higher standard of living. To do so with today’s global fossil-fuel-industrial complex might lead to a global warming like the one that destroyed 95% of the world’s species 250 million years ago in the Permian Extinction.[14] At the same time, the global elite seem intent on pushing most of the people in the Rich regions down into the lower-middle class, if not into global poverty. What is to be done? Can humanity be saved? Can the planet be saved? Tune in next time, as we witness another episode of….Extreme Makeover, Global Edition! You can contact Jon Rynn directly on his jonrynn.blogspot.com .

You can also find old blog entries and longer articles at

economicreconstruction.com. Please feel free to reach him at

This email address is being protected from spam bots, you need

Javascript enabled to view it

. Footnotes

[1] Lester R. Brown, “Plan B 2.0: Rescuing a planet under stress and a civilization in trouble”, 2006, W.W. Norton. See also Chris Sanders, “The World in Depression ?” [2] http://pubs.giss.nasa.gov/docs/2003/2003_Hansen.pdf [3] Jared Diamond, Collapse: How societies choose to fail or succeed , 2004. [4] For example, the geopolitical scientist, Nicholas Spykman, which includes a discussion of Mackinder as well. [5] Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The fates of human societies , 2005 [6] See, most recently, the eminent but fairly conservative economic historian, David Landes . [7] Eugene Ferguson, Engineering and the Mind’s Eye , 1994. [8] Nathan Rosenberg, “Technological Change in the Machine Tool Industry, 1840-1910”, Journal of Economic History , December 1963, reprinted in Nathan Rosenberg, Perspectives on Technology, 1976. [9] “Before the Economy Hits the Fan: Why we need a new progressive agenda”, and “The Rise and Decline of the Great American Corporation ”. [10] “Say Dubai to the American Economy ”. [11] Ludwig Dehio, The Precarious Balance: Four centuries of the European power struggle , 1965. [12] David Calleo, The German Problem Reconsidered: Germany and the world order, 1870 to the present , 1980 [13] The data on which the following tables is based has been compiled in a spreadsheet where the countries for each region are listed, along with GDP, population, and world percentages. These data in turn are based, for the most part, on UN Data. Sources: the population data for 2005; and the economic data , “GDP breakdown at current prices in US Dollars (All countries)”, 2004. [14] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permian-Triassic_extinction_event%20 |

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|